Any one who has struggled with an addiction knows the experience summed up in the phrase “I can’t not.” Addiction divides the person into two: one who knows that he does not want to drink the gin, watch the porn, eat the chip; the other who wants it more than life itself. The former watches in horror while the latter gratifies himself.

Of course, this description is a lie formulated to survive the shame of addiction: There is no interior addict. There is no guilty, binge-eating “other” who afflicts an innocent, healthy self with his disordered desires. There is one person, one will, and one capacity to say “no.” But addiction has a theater of its own. On its stage, man is divided against himself, a two-headed monster who watches and recoils at the very thing he does.

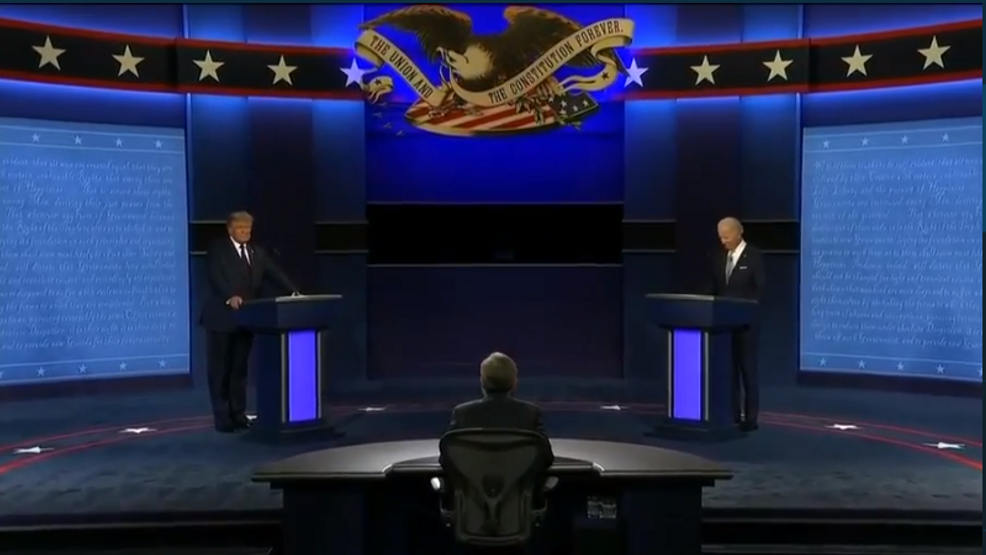

Our country has an addiction. I felt it, having made the miserable choice to watch the presidential debate. I saw sin and ignorance plated and served as our election dish; I cringed and blushed at the malice of the two candidates, who may as well have held up their middle fingers in a minute of silence to their respective cameras, signifying to “the folks at home” that they knew we were all too stupid and vicious to care for any defense of policy; any description of their purposes beyond hollow promises to give us more stuff; any debate beyond geriatric bitching; any language beyond garbled, broken sentences fit only for mobs too loud to hear anything but key words and too drunk to respond except in jeers and cheers.

But even as I saw what no preacher worth his pulpit would hesitate to call sin, I heard that deadly whisper of “I can’t not.” I can’t not vote for one of these two men. The reason has been ceaselessly impressed into my hippocampus: you cannot waste a vote. A vote for a third party, no vote at all: these are esoteric votes for the evil you despise. A vote for not-Trump is a vote for Biden, and vice versa. So eat the chip; watch the porn; learn to cheer what half-sentences you can discern. Joke about it. Become two people. Say things like, “I’m holding my nose!” and vote nonetheless, because I have an addiction, and you do too.

Let’s presume the truth of this particularly psychotic claim; the panicked proposal that, due to the unlikeliness that something new will happen, one should not try anything new. Let’s nod, dreamily, to the sagacious sounds of our political death-trap, which has given up on even pretending that something resembling a virtuous leader is at the end of our tunnel. Let’s grit our teeth and prepare for rapidly diminishing returns; for the freefall we are not allowed to stop, lest we unwittingly speed it up. Let’s only ever choose the lesser of two evils until, in America’s last election before the Eschaton, people of good conscience unanimously reject Lucifer and name Beelzebub as their President. Still, I don’t want to be an addict any more. I want to get free. Something has to change.

You can’t break an addiction without exiting its world. Priests say as much when they say “avoid near occasions of sin.” Therapists say as much when they say “change your environment.” Any addict I’ve met has repeated this wisdom: You can’t get clean when your rehab is two doors down from a crack-house. If Catholics are suffering an addiction to the political status quo, voting as we would not and unable to do otherwise, we are not going to break its chains by ignoring the screams against vote-wasting and selecting Kanye West as our leader. Rather, we need to avoid the near occasion of national elections; we need to change our political environment; we need to exit the world that our addiction has built. We need to fulfill our nature as political animals differently than just another embarrassing national election.

Here is what I suggest. There are 19,495 incorporated villages, towns and cities in America. Of these, 14,768 have a population of less than 5,000. Let us shake off the shame of our addiction and take up political offices in 100 of these towns by November 2021.

By “let,” I mean let’s go.

By “us,” I mean Catholics who believe that something new is necessary for our country; who desire to see the social teaching of the Catholic Church realized in their community; who think that the political order of liberalism is bad; or, more simply, who desire to lead their friends, families, neighbors into greater goodness and virtue through the prudent use of political authority.

By “take up,” I mean to win elections or volunteer for positions, donating any salary or compensation back to one’s city, town or village wherever possible to secure trust and goodwill from a people increasingly skeptical that a politician could have anything but his self-interest in mind.

By “political offices,” I mean those commonly recognized positions in which one can efficaciously protect and attain common goods and lead others into greater virtue, whether as councilman, parks and recreation director, mayor, or city engineer; on village councils or in governors’ mansions.

By “in 100 of these towns” I mean precisely what I say, with an emphasis on villages, towns and cities in which winning elections would be genuinely possible, if not easy.

It doesn’t matter if you run as an Independent, Democrat, Republican, or an American Solidarity Party candidate. Parties only take on moral weightiness within the addiction of national elections. A pro-life Democrat is impossible on a presidential scale, but it’s typical in Rust Belt towns. A union-loving Republican makes no sense, nationally, but I can introduce you to several, locally. The two-party system thrives on its theatrical fetishization of the national over every other level of government. Don’t fall for it: do whatever will work.

Do not be afraid of not having money: locally speaking, personal reputation and earnestness matter more than money. Do not waste your time on some much-sought, well-paying, glamorous office; be drawn to weakness and brokenness, the ideal conditions for showing forth the efficacy of Christian politics.

Run, win, take office, and work hard on creating the material conditions necessary to lead others into virtue, through the instantiation of Catholic social teaching, in whatever capacity given to you. Upon winning, contact us showing and explaining your new position, and we will add you to a forum of new politicians who can collaborate on the effective instantiation of Catholic social teaching in their home. The idea is not to dictate or suggest concrete, local action, but to advise, pray and support each other as new politicians, in solidarity and subsidiarity. The idea is not to have a brand or a new party: keep your own affiliation as quiet or as loud as you like.

Once a hundred-towns-strong, let’s increase, until we have our people in fourteen thousand cities, towns and villages, all about the same business of keeping the peace and the faith, connected to each other in mutual bonds of charity and prayer. To intentionally incarnate Catholic Social Teaching is an end in itself; and to put workers in fourteen thousand vineyards needs no justification. But lest my meaning be confused, let me clarify. This is not to neglect or dismiss the importance or reality of national politics and its associated elections. This is political realism. To begin by trying to do politics at the national level is to ensure that one will never be called upon to do politics; to think primarily in terms of national elections is a safety net that ensures that Catholics will never be granted political authority, along with its duties. No one different wins a national election. Becoming liberal is a prerequisite to attaining to real power within fundamentally liberal institutions, from the Supreme Court to the White House. The only Catholics that take political authority in D.C. do so by assuring the public that the Church matters to them as a personal conviction and a private club. This is not the case locally — or at least not as often. Neighbors do not tend to demand oaths of fealty to the philosophy of liberalism. Local questions involve real goods and your ability to secure them; real evils and your ability to defend against them; if you do so to usher in the social kingship of Christ your neighbors will, at worse, view you as a useful nut and at best, convert and understand the spiritual power of the Church as a better source of peace than the violence of liberalism.

Turning to local politics makes Catholic politics real, and in two ways: by actually risking victory, and so becoming responsible to lead a community into greater virtue, and by creating the necessary condition for Catholics to ever win national elections as Catholics — rather than as liberals for whom the Catholic faith has been relativized into a pleasant, private conviction.

For I know of no other way than the way of hard work; of no other start than to start small; of no haul but the long haul; and no way to take Washington D.C. than to muster new politicians outside of that particular swamp, and on the basis of different principles than those D.C. requires. At fourteen thousand towns strong, we could start a new party, produce a new candidate — having already produced a broad coalition and borne political fruit where we live.

Let us change our environment, turning from the shame of the presidential debates to our immediate, profound duty to lead others to virtue and fulfill our natures as social, political animals in the pursuit of the common good; not casting off this duty onto a national victory that never materializes, but taking up the offices that we can enter with real, immediate efficacy. When you do it, let us know.